Reflection is a learning experience in itself. It allows us to critically assess the ways in which we can improve. This is extremely valuable in the context of medical education where we need to draw learnings from both academic training and medical practice. Earlier this year, Professor Olle ten Cate delivered a public lecture at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland titled, What is a 21st Century Doctor? Professor ten Cate took time to reflect on how medical education has changed over the last century, and how it could evolve in the future.

It was suggested we are reaching a tipping point in how we teach medicine. Medical curricula, whether legacy or brand new, needs to be reviewed and adapted every five to six years. Disruptive innovation is already playing a factor and we need to plan for it. Professor ten Cate stressed,

"Competence is more important than the duration of education."

The relationship between the medical degree and the length of training has become a topic of discussion in recent years. We are seeing an increase in specialisation in medical training and Professor ten Cate stated this is leading to the fragmentation of healthcare. The medical degree is regarded as a ticket to the next stage of training. The generalist training that is achieved after a medical degree is being pushed aside to pursue years of specialisation training, to the point where one MD is replaced by 40 to 50 sub-specialties.

It must be acknowledged we cannot teach everything, and graduates cannot be expected to learn it all. Educators should strive to produce different, flexible graduates. Professor ten Cate believes we need more generalists, more GPs. This trend is thankfully re-emerging, where there was previously a trend towards sub-specialties. He feels students should be proud to be generalists and to enter practice.

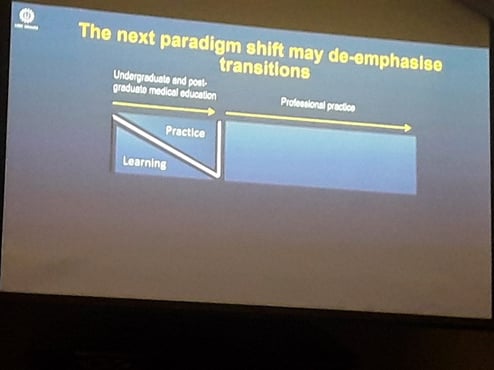

A key change in this process would be to de-emphasise the transitions between learning and practice, and professional practice. Clinicians need to make teaching and learning part of their professional life.

"Training and education should not be bound within training institutions, we all need to make time for education."

The identity of what a physician is may need to change. Training should be seen as on-going. If this transition is not de-emphasised, by the time training is over, physicians may not be ready to deal with patients for unsupervised practice. Professor ten Cate introduced the concept of Entrustable Professional Activities at this point.

Entrustable professional activities (EPAs) translate competencies into clinical practice. Competencies reflect the clinician's ability to complete a task successfully and efficiently. They encompass both education and clinical outcomes. EPAs then act as descriptors of these competencies, allowing progress to be measured. EPAs facilitate the crossing of boundaries between undergraduate, general medical education and professions.

Professor ten Cate stated as a result of this process, more rounded graduates should emerge. To illustrate this transition, a move from a H-shaped curriculum to a more modern Z-shaped curriculum was presented. In the first scenario, classroom teaching and workplace learning are divided into separate stages. The second scenario allows the graduate to enter practice and gain clinical experience while embarking on a journey of on-going learning throughout their career.

Without this expectation of on-going learning and continuous measurement of competencies how can we be sure clinicians are being presented with opportunities to further develop and perfect their skills? A difficult question we encourage our clients to include in their assessments was then posed to the audience.

"Have you ever certified someone you weren't completely comfortable with? "

Thank you to Professor ten Cate for an excellent lecture.